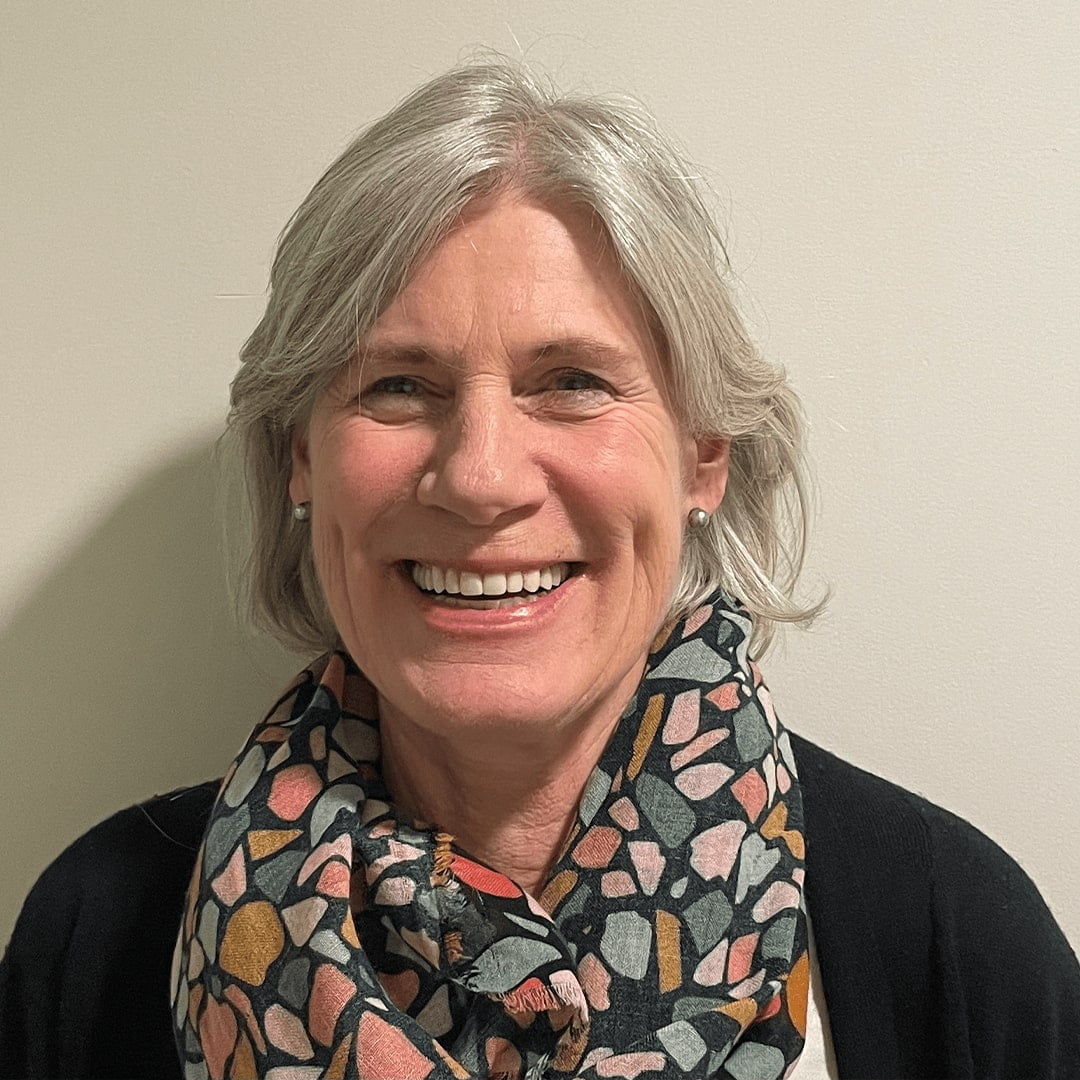

Professor Cliona O’Farrelly, Professor of Comparative Immunology at Trinity College Dublin, will join the Lister Institute Scientific Committee this September.

Cliona is renowned for her work in comparative immunology and the inspiring and supportive influence she has on young scientists beginning their careers at Trinity. Her work on liver and uterine immunology has led to new insights into how immune mechanisms in these organs protect against viral infection, cancer and infertility.

Cliona’s appointment marks another point of connection between the Lister Institute and Ireland’s celebrated Guinness family. The Institute was founded on charitable donations, including a huge sum from Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh and then head of the Guinness family. Lord Iveagh contributed £250,000, equivalent to around £15,000,000 in today’s money, which went towards building works and funding staff salaries and scholarships. The Guinness family has been represented on the Governing Body ever since.

Cliona’s early days in academia were also connected to Guinness family philanthropy. Her undergraduate studies took place at the Moyne Institute of Preventive Medicine at Trinity College Dublin, which was founded by the Guinness family in memory of Walter Edward Guinness, First Baron Moyne.

“It’s so exciting to welcome Cliona to the Lister, building on our historic links to Trinity, Dublin and Ireland,” said Rory Guinness, Lord Iveagh’s representative on our Governing Body. “Her work is so pertinent and important that it’s wonderful that she finds time to give to the Lister Institute.”

We caught up with Cliona to talk about her achievements in immunology and her connection with the Lister.

What made you choose immunology as a field of study?

I had decided I wanted to be a town planner and needed to do architecture and I also really, really wanted to go to Trinity College Dublin, Ireland’s oldest and best university . It was only when filling out the application form and looking under ‘A’ for architecture in the syllabus, that I realised Trinity didn’t have a school of architecture. I needed to get down to the post office to send the form, and I spent all afternoon wondering what to do – law, French, history? I knew I was good at science so that’s what it had to be, if I wanted to go the Trinity. However , science didn’t really click for me until I got into the Moyne and started concentrating on the world of microbes and how the body responds to them. I had wonderful inspiring lecturers, and I did my undergraduate project in immunology: I was caught for life.

Immunology has a huge role in medicine, and probably more diseases are controlled through the immune system than any other route. Treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases has been revolutionized by immunotherapies, but there are also many other diseases with an inflammatory component, like diabetes and heart disease.

Tell us about the immunology degree courses you started at Trinity.

A few of us helped to set up an undergraduate degree in immunology. Trinity had several wonderful scientists including, Luke O’Neill, who is a Royal Society member and a brilliant world-famous immunologist, and Kingston Mills, another world-renowned immunologist, as well as others which meant that we could run a course.

I started an MSc in immunology for those who come from other subjects like biochemistry, medicine, physiology, botany or engineering and want to take your studies in an immunological direction. Many of the world’s leading pharmaceutical companies have European bases in Ireland. So, because of that, and because of the power of immunology, we also set up a master’s in immunotherapy that is very successful.

Your research career has focused on liver immunology. What made you choose that specialism?

Before I returned to Trinity as Chair, I ran the research labs in one of Dublin’s largest teaching hospitals, St. Vincents, which also happens to house the National Liver Transplant Programme. When I started there in 1993, I got great advice from a very good friend and colleague, Richard Gallagher, now editor of Advances who said ’align your research with something that the hospital is famous for.’ The hospital was just taking off as a centre for liver transplantation. I remember thinking to myself, I have a degree in microbiology, a PhD in immunology, but no nothing about the liver.

I started to ask questions about liver transplantation and discovered that liver transplant teams don’t match for HLA (human leukocyte antigen), which helps determine if a patient will accept an organ from a particular donor. It turns out , the liver is rejected less easily than other large organs and liver transplant patients only need one-tenth of the immunosuppression. This fascinated me.

I thought to myself, I bet one of the reasons why that’s happening is because there are immune cells in the liver. The Prof of pathology at the time said that there were no lymphocytes in healthy liver there are lots of macrophages and Kupffer cells but no lymphocytes. So, we went looking and found lots of lymphoid cells in healthy liver, including major populations of NK cells. We were amongst the first in the world to start describing the lymphoid system in the liver.

What is your lab investigating?

The main thrust of the lab at the moment is resistance to viral infection. We have made an interesting discovery about women who were resistant to hepatitis C when they received contaminated Anti-D medication – we found that they have a particularly effective interferon response. Out of that discovery grew a conviction that some people would be resistant to SARS-CoV-2, so that’s what we’re looking at currently.

How did you first connect with the Lister Institute?

Over the years, I had heard about the Lister Institute supporting Irish researchers as it had been set up before Great Britain and Ireland separated. Then one of Trinity’s best upcoming researchers, Tomás Ryan, became a Fellow last year. Also, I collaborate a lot with researchers at the Pasteur Institute, which was the first of its kind in the world. So having started my academic life in one institute of preventative medicine and finding so many kindred spirits at the founding institute of preventative medicine, it is an honour and a privilege to also be able to serve the Lister Institute.

What are your hopes for the Lister Prize and its Fellows in the future?

I’m really interested in the democratisation of knowledge, giving everybody the tools to understand what’s going on in science, in their bodies and in the world. That’s something I would like to promote – helping the Lister Fellows communicate their work. Not everybody is comfortable doing that and some are wonderful, so it’s about identifying the people who are and finding ways to support them. That way, we might promote knowledge and an appreciation for why discovery science is so valuable for us all. In these days of pandemics, antibiotic resistance, AI and climate change, many people are really interested in the power of science and how it might make the world a better place – we must catch this wave.

Learn more about Cliona’s work: https://www.tcd.ie/Biochemistry/people/ofarrecl/